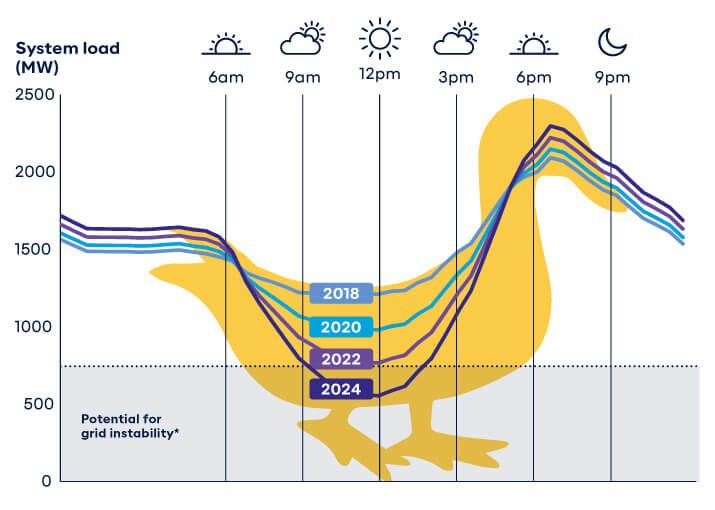

The electric duck curve is a graph of power production over the course of a day that shows the timing imbalance between peak demand and power generation. Most of the time this curve has been used to illustrate solar power generation.

Typically, power companies supply the least amount of power at night when most of us are sleeping and ramp up generation during the morning as people wake up and businesses get going. Then, at sunset, the energy demand peaks and the cycle repeats. The introduction of solar power, however, has brought about some problems in these demand curve models.

Peak solar production occurs around midday when the sun is at it’s highest but also when electricity demand is often at the low end. As a result, energy production at this time is greater than demand. When evening approaches, solar production falls off and by 7 PM, can provide very little electricity when the demand is at it’s greatest. This discrepancy results in a net demand curve that takes the shape of a duck, and the duck curve gets more pronounced each year, as more solar capacity is added and our net demand dips lower and lower at midday.

This drop in net demand at midday basically creates two problems: First, since solar energy production wanes as demand for energy is peaking, the utilities have to ramp up production to compensate for this gap, often overstressing a grid that is not yet set up for these peaks. Second, baseload sources of energy, like nuclear and coal, need to run 24/7. Turning them off at mid-day is economically unfeasible, so the solar, wind, and gas power sources must be offloaded. In some states, especially in the spring and summer, solar power is being wasted to avoid overloading or even damaging the grid.

As more solar capacity comes online, conventional power plants (nuclear, coal-fired, and natural-gas fired) are used less often during the middle of the day, and the duck curve deepens.

The extreme swing in demand for electricity from conventional power plants from midday to late evenings requires those plants to quickly ramp up their production to meet the demand. This increase in demand is often greater than the ability of these conventional power plants to ramp up their generation. Therefore, anticipation of the demand requires these plants to begin their ramp up sooner than the actual demand in order to have the power available when required.

Ultimately, decreasing the contribution from solar and/or wind must be manipulated by the grid operators to meet the forecasted demand, which in turn drives up the costs.