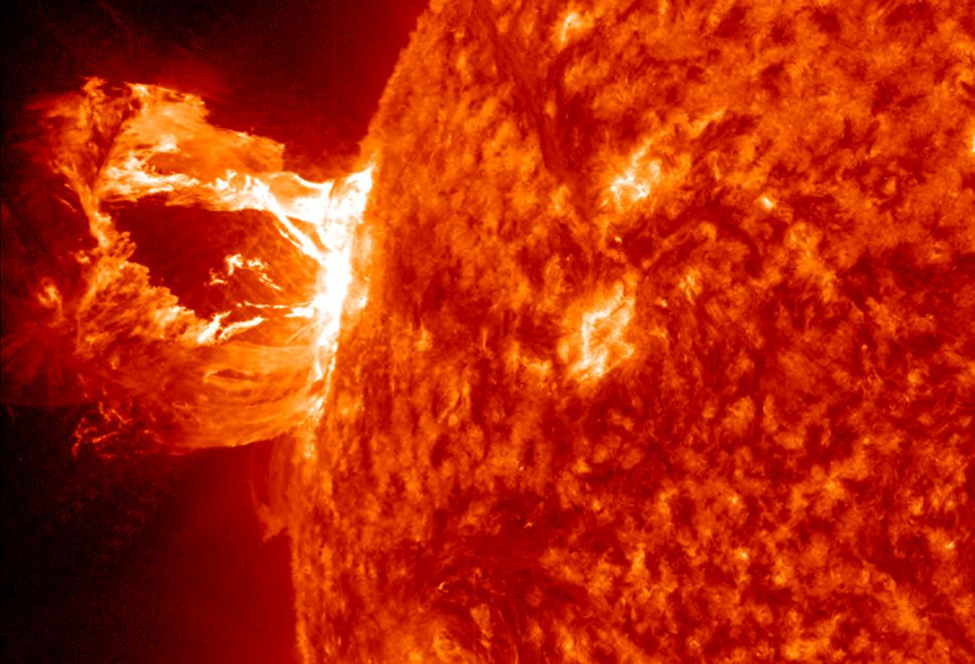

Solar storms are becoming more frequent and powerful as the sun nears the peak of its 11-year solar activity cycle. In 2022 we had an abundance of solar storms – some surprises with massive sunspots and others producing vibrant aurora explosions and rare observable phenomena.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, rates solar storms from G1 to G5 (i.e., G1, G2, G3, G4, G5 in order), where G1 is the weakest storm classification.

One storm in 2022, only a G1-class event, crashed into earth without warning causing many scientists to scratch their heads. Why? Because storms like these usually come from a coronal mass ejection (CME) – a burst of plasma with an embedded magnetic field that is belched out from a sunspot – but in this case researchers couldn’t find any evidence that a CME occurred. A G1-class event is significant because it is strong enough to create weak power grid fluctuations, cause minor impacts to satellite operation, disrupt navigational abilities of some migrating animals, and cause unusually strong auroras.

A particularly strong solar storm could have devastating effects on undersea internet cables, a crucial component of the world’s internet infrastructure. Without stronger mitigation efforts against these effects, the study claims we could be headed towards an “internet apocalypse.”

Massive solar tsunamis on the surface of the Sun can send particularly strong CMEs hurtling towards Earth at speeds of up to several million miles per hour. While the Earth’s atmosphere protects us against the radioactive effects of such storms, they can cause havoc to our electronics.

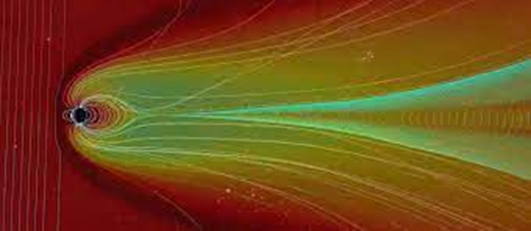

These solar superstorms have the potential to cause long blackouts, as solar winds batter the Earth’s magnetosphere causing millions or even trillions of dollars of damage to electrical equipment including satellites. And it’s not just a hypothetical scenario. In 1989, a solar storm was responsible for cutting off the electrical supply to over 6 million people for nine hours in and around Québec. It even halted the Toronto Stock Exchange for three hours by disrupting what was supposed to be a “fault-tolerant” computer.

Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi of the University of California, Irvine presents a hypothetical scenario in her paper, titled “Solar Superstorms: Planning for an Internet Apocalypse”. She presents in her hypothetical scenario how an internet outage could persist for long periods after a strong solar storm, even lasting for prolonged periods after power returns to the grid.

Abdu Jyothi states that regional internet infrastructure is actually surprisingly robust against solar storms. This is because optical fiber isn’t affected by the geomagnetically induced currents that are typical of solar storms. However, the electronic repeaters used to amplify the optical signals in long undersea cables are very vulnerable to those currents, and a strong solar storm has the potential to cut worldwide connectivity by disrupting these cables.

In an interview with WIRED, Abdu Jyothi pointed out that she started thinking about the effects of solar storms on our internet infrastructure when she saw how unprepared the world was for the COVID-19 pandemic. “Our infrastructure is not prepared for a large-scale solar event. We have very limited understanding of what the extent of the damage would be,” Abdu Jyothi explained.

Luckily for us, geomagnetic storms are relatively rare, we only have data from three large events in relatively recent times: the previously mentioned 1989 Québec outage, and events in 1921 and 1859. All of these occurred before the advent of the modern internet.

Not only are undersea cables vulnerable, but services such as SpaceX’s Starlink satellite internet service would also be particularly vulnerable to a solar superstorm, as they orbit 340 miles (550 kilometers) above the Earth’s surface. Abdu Jyothi points out that there are currently no models for how exactly a strong solar storm would play out in today’s internet-reliant environment. She hopes her study will lead to a renewed focus from global industries on the potentially destructive effects of solar storms on our world’s connectivity.

Crucially, Abdu Jyothi says that as the last strong solar storm occurred over three decades ago we may be close to the next incident that could cause massive outages, potentially leading to trillions of dollars in damages to electronics and lost revenue from internet blackouts — according to Forbes, internet outages could cost $7.2 billion per day to the US economy. This is a number that will only rise, particularly as the world has increasingly turned to remote work amid the ongoing pandemic.

Scientists have warned that we are overdue for one of these blasts to result in the induction of electrical currents throughout the planet – called a GMD (geomagnetic disturbance).

We first learned about “geomagnetic storms” on September 1, 1859, when solar astronomer, Richard Carrington, witnessed sunspots that suddenly and briefly flashed brightly before they disappeared. Just before dawn, the very next day, auroras erupted over most of the Earth, as far south as the Caribbean and Hawaii, while the southern lights were seen as far north as Chile.

This event, named the “Carrington Event” not only produced a visible light show in areas where they had never appeared, it also caused electrical shock to telegraph operators, shooting sparks out of pylons, and causing paper fires.

Today, such an event could grind our technological infrastructure to a halt by overloading, disrupting, or knocking-out some of our modern technologies, like satellites and cellphones. A very real threat to our electrical infrastructure and power grid due to grounding and digitalization of equipment and components.

Since our electrical grids are grounded, they are susceptible to electrical currents induced from these storms, deep inside the Earth. Although the voltage is relatively low – just one or two volts – our power transmission lines extend for miles, and some of these lines are hundreds of miles long, so this voltage can add up and become significant. Just how significant is dependent on the size of the storm and the specific geology of an area or region. In the U.S. we are most vulnerable in the Midwest and Northeast.

In addition, the resultant voltage is more like direct current, which can result in transformer coil heat up – frying the coils – resulting in a loss of that specific transformer. And, when power transformers go down, the damage is rarely isolated, disruptions can ripple across the power grids and cause a major catastrophe.

Luckily, most geomagnetic storms are smaller in strength than the “Carrington Event”. These smaller storms occur more often – every 100 years or so – five times more frequently than a 500-year storm like the “Carrington Event”.

NASA says we have a 10% chance of a GMD event – similar to the “Carrington Event” – this decade. We just barely missed one in July 2012.

Today, should a “Carrington Event” occur, it is estimated, that it would inflict $2 trillion worth of damage and a recovery effort that could drag out for months or years – affecting the world.

Photo Credit: NASA/GSFC/SDO

Artist Conception of Carrington Event