The corporate mission to secure vast amounts of renewable energy faces some big challenges, especially in the Southeast, one of the country’s fastest-growing renewable regions. Is what is good for a few companies good for all?

The corporate mission to secure vast amounts of renewable energy faces some big challenges, especially in the Southeast, one of the country’s fastest-growing renewable regions. Is what is good for a few companies good for all?

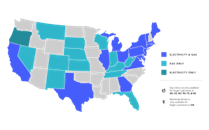

These corporations want the Southeast electric utilities to become deregulated to develop a power market. In the last 30-40 years, over 20 U.S. states have deregulated their energy markets, starting with natural gas in the 1970’s

One corporate example is Google – they have a major concentration of data centers in the Southeast where the utilities are still regulated. Google and their tech giant allies want to dismantle the decades-old regulatory system and replace it with an electricity power market where energy companies compete for their customers, like the deregulated states.

Years ago, most electricity in the United States was generated and distributed by the regulated utilities within each state. However, just before the start of this century, many states deregulated the utilities, arguing that competition would bring efficiency – this action bypassed the Southeast.

When utilities are deregulated, you as the customer, choose which utility or energy provider you want to supply your needs. This is all good from the customer’s perspective when the costs are low and there is good competition. However, deregulation is a two-edged sword. For example, recall when Gray Davis was Governor of California (1999 – 2003) and California desperately needed power. They wound up paying up to $1,500/Mw-hr versus the nominal $50-60 Mw-hr at that time.

Here is an excerpt from Governor Davis’ interview with Frontline. “There’s no question that the law passed in 1996 was flawed. It deregulated the wholesale market, meaning the price that the utilities had to pay energy companies for power, but not the retail market. As a matter of fact, it reduced rates to customers and froze them for five years. So that was an inherent conflict. In 1999, the entire state – including public power authorities at municipal levels – spent $7 billion on power. In 2000, a year later, for approximately the same amount of electricity, $32.5 billion – a 450% increase.”

The Southeastern utilities staunchly defend their position – senior executives contend that their system better insulates the consumer from spikes in prices of commodities (such as the recent spikes in cost for natural gas), promotes reliability, and supports the long-term investments needed to develop clean-power technologies. Thomas A. Fanning, chief executive of Southern Company, Georgia Power’s parent company, said in an interview, “We absolutely are superior in every regard to those markets over time”.

Tom Davis, a Republican state senator in South Carolina spearheaded a law passed in 2020 to explore setting up an electricity power market. He said, the current regulatory system financially rewarded utilities even when they messed up. “It’s not incentivizing them to go out there and try to find somebody who’s built a better mousetrap and can generate power more cheaply”.

However, Caroline Golin, Google’s global head of energy market development and policy, offered another option at a legislative hearing in July, raising the possibility of South Carolina’s breaking out of the Southeast utility system altogether, and joining the PJM. The PJM was started in 1927 and it is a regional transmission organization (RTO) that coordinates the movement of wholesale electricity in all or parts of 13 states and the District of Columbia. Originally the Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland (PJM) interconnection – it has continually grown into its current organizational structure.

The larger utilities in the Southeast are now building more solar projects, but those pushing for a deregulated electrical power market say it’s not enough. Their proposed solar projects’ have a generating capacity equivalent to ~25% of their total capacity, far below the 80% needed for the PJM, according to an analysis by Tyler Norris, a senior executive at Cypress Creek Renewables, a solar company, and a special adviser in the Energy Department during the Obama administration.

One criticism offered about regulated utilities is that they are rewarded for building unneeded generating capacity because this in turn increases their base, on which their electric rates are set. Ms. Golin said a deregulated power market would remove that incentive and cut costs without affecting the system’s resilience under stress, based on Google’s experience in areas with power markets.

But executives at the Southeast utilities say their reserve capacity contributes to their higher scores in a national assessment of reliability – an increasing concern as climate change produces more extreme weather events. They also point out that one of the biggest failings of power markets is that they don’t support the operation and building of nuclear plants, which, the executives say, will provide uninterrupted carbon-free energy that will shore up the reliability of their grids as more intermittent renewable energy is introduced. The revenue streams in the more regulated system provide the financial stability to support nuclear plants, they contend.

“We’re the only utility building a nuclear plant in America,” Mr. Fanning, the Southern chief executive, said. “Couldn’t have built it in the PJM or ERCOT.” Nuclear plants in operation are giving the Southeast region some of the highest carbon-free scores in the country. Over 60% of South Carolina’s generation was carbon-free in 2021, most of it from nuclear plants, compared with 35% in Texas, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

So, all in all, it boils down to our introductory question; Is what is good for a few companies good for all?

Photo Credit: New York Times